A history-making friendship

“Boozhoo” — or greetings in the Chippewa language — to this site devoted to the intertwined lives of Lake Superior tribal leader Great Buffalo and entrepreneur and interpreter Benjamin G. Armstrong, his “adopted son” who also married into the chief’s family.

Here, read about adventures of two men from different worlds who found friendship and common purpose in the 1800s woodlands frontier.

The 1852 Journey to Washington. Chief Buffalo, Benjamin Armstrong and five tribal members on April 5, 1852 departed by canoe on a 10-week journey from an island in Lake Superior to Washington, D.C. Federal agents repeatedly told them to go home. But the delegation was determined to reach the nation’s capital to make sure the federal government’s promises were kept and to stop the possible removal of the Lake Superior Chippewa from their homes to lands to the west. Failure could result in battles back home. The group arrived in New York with a just a dime left in Armstrong’s pocket and raised money to complete their trip by exhibiting themselves in high society parlors. Click here to read more in Benjamin Armstrong’s own words

Chief Buffalo’s busts in the U.S. Capitol. Chief Buffalo on a second trip to Washington in 1855 was paid $5 to sit for a clay modeling. It would later be used to create a marble bust for the Senate side and a bronze bust for the House side of the Capitol. Two busts of Chief Buffalo have been on display in the Capitol for more than 150 years — a rare honor in American history. A U.S. Senate document from today says: “This formidable Native American was also called Great Buffalo, and the adjective was clearly deserved.” Click here to read more about how these works of art came to be

The Sandy Lake Tragedy, also called the Chippewa Trail of Tears and the Wisconsin Death March. The tragedy occurred when government officials in 1850 moved the annual treaty payments from Madeline Island in Lake Superior to a location hundreds of miles to the west in the Minnesota territory. The change was part of a bigger scheme to relocate the tribe. Delayed and meager payments, lack of supplies, tainted food, disease and the onset of winter resulted in the deaths of hundreds of Chippewa people. Its aftermath is one of the reasons for the 1852 journey to Washington made by Chief Buffalo and Benjamin Armstrong. Click here to read more about the Sandy Lake Tragedy

The Buffalo Tract and Duluth land claims. Chief Buffalo via the Treaty of 1854 gave Benjamin Armstrong the right to large tracts of land, including an area that now is the Lake Superior city of Duluth. What happened to it? The land disputes later were at the center of two U.S. Supreme Court cases, the focus of newspaper stories, and even the subject of a song available on iTunes called “Landlord of Duluth.” Click here to read about the land claims

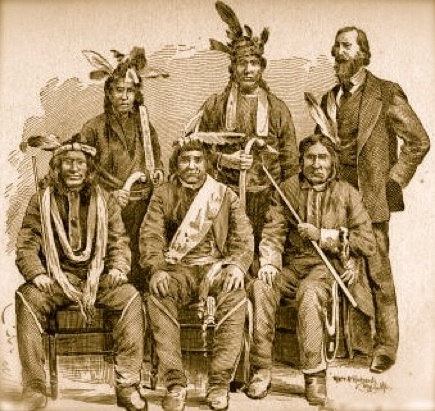

Meeting with President Abraham Lincoln. President Lincoln’s Commissioner of Indian Affairs appointed Benjamin Armstrong as a special interpreter. Armstrong selected nine Chippewa chiefs from Minnesota and Wisconsin to meet with the president in the early years during the Civil War. Lincoln told them: “My children, when you are ready, go home and tell your people what the great father said to you; tell them that as soon as the trouble with my white children is settled I will call you back and see that you are paid every dollar that is your due.” Click here to read more about the meeting with Lincoln

The Apostle Islands and the Chequamegon Bay region of Wisconsin. This area was central to the lives of Chief Buffalo and Benjamin Armstrong. Madeline Island is the spiritual center of the Chippewa religion and Buffalo’s birth and burial resting place. Armstrong had a store in La Pointe and has been called “one of the most intriguing characters in the history of the Apostle Islands” and “the chronicler of Ojibwe history in the Apostle Island region.” Benjamin’s connection to other islands in the chain included homesteading and commercial logging on Oak Island and befriending the recluse of Hermit Island. Click to read more about the Apostle Islands and their lives on them

Oak Island. One the Apostle Islands, Oak Island had a central role in the lives of Benjamin Armstrong and his family for many years. More than 160 years ago, they arrived on Oak Island to start a new life. They built a home and dock and established a trading post on the island. They cleared land, farmed it and sold wood to steamers traveling Lake Superior in the years before coal became the fuel of choice. A National Park Service publication says Benjamin “Armstrong was among the first to engage farming activity on an Apostle island other than Madeline Island when he farmed the five acres on Oak Island beginning in 1855.” It further notes: “Logging for a broader market began on Oak Island during the 1850s, when Benjamin Armstrong began cutting hardwood for steamboat fuel.” It adds, “Benjamin Armstrong is the best known of the traders who were working in the Chequamegon region in the 1850s.” The “Visitor’s Guide to the Apostle Islands National Lakeshore” notes Armstrong “was one of the framers of the economy in the Chequamegon area.” Click here to read more about the Armstrong Family and their years on Oak Island

Tribal Voices. How do Chippewa tribes describe Chief Buffalo and the Treaty of 1854? Click here to read more and for Web links to tribal government sites

Armstrong Memoirs. The Wisconsin Historical Society in the 1970s worried that the 1892 book “Early Life Among the Indians: Reminiscences from the Life of Benj. G. Armstrong” literally would crumble away and printed a four-part extended excerpt in its official magazine. Today, Google and others have digitized Armstrong’s memoirs to preserve it for generations to come. His work not only documented life in the woodlands frontier of the Lake Superior region in the 1800s, it helped create history in the next century when a federal court cited the memoirs in a ground-breaking decision in federal Indian law. We have found that some dates in the 1892 book may be slightly off. Benjamin Armstrong noted when writing the book: “This undertaking I begin, not without misgivings as to my ability to finish a well connected history of my recollections. I kept no dates at any time, and must rely wholly upon my memory at seventy-one years of age. Those of my white associates in the early days, who are still living, are not within reach ... Those of the older Indians who could assist me, could I converse with them, have passed beyond the Great River ... Therefore, without assistance and assuring the reader that dates will be essentially correct, and that a strict adherence to facts will be followed, and with the hope that a generous public will make due allowance for the lapse of years.” Click here to read more about his memoirs

Their lives. Chief Buffalo and Benjamin Armstrong lived in the Lake Superior frontier, but individually or together the men met with three U.S. presidents. Chief Buffalo is considered the greatest of the Lake Superior chiefs and guided his people through a period of change. Armstrong has been called “the best known of the traders who were working in the Chequamegon region in the 1850s” and “one of the framers of the economy in the Chequamegon area.” History books, legal materials and other documents have cited Armstrong’s 1892 memoirs, “Early Life Among the Indians: Reminiscences from the Life of Benj. G. Armstrong.” Benjamin Armstrong’s legacy today is not with controversy, ranging from attacks by anti-treaty activities who dispute the use of his memoirs in courts of law, to one scholar who suggests Armstrong ultimately played a negative role in the loss tribal land in present-day Duluth. Click here to read more about their lives

About This Site. This Web site is a work in progress. Please e-mail ideas, information or corrections. All Web links on this site were current as of March 2016. Click here to read more about this site

Note about terminology: The Chippewa are one of the largest tribal groups in North America. The English and later the U.S. government used the name Chippewa. The words Ojibwa, Ojibway and Ojibwe are said to French versions. Tribal members also use Anishinaabe, Anishinaabeg or variations, meaning the first people or the original people. For consistency’s sake, this site generally will use the word Chippewa, except where book titles and other quoted materials use other names.